Julian Motau: A Voice. A Vision. A Very Short Life

Early Life and the Move to the City

Julian Motau was born in 1948 in the rural region of Tzaneen, Limpopo Province, South Africa. His childhood was shaped by the rhythms of rural life, but also by limited access to formal education and the growing tension of apartheid‑era policies. From early on, he felt the weight of inequality and the realities of forced relocations, poverty, and social marginalisation. At just around age 15, he moved to Johannesburg in search of opportunity but also, quietly, to find a voice. That move set the stage for his art: urban, raw, observing lives often unseen.

What Drove Him

Motau’s driving force was the stark contrast between what he saw and what he felt was right. He witnessed township life crowded, constrained, under pressure—while society around him often turned a blind eye. His art became a way to speak back: to show the human cost of policies, of structures, of neglect. He taught himself much of his drawing and technique, refusing to wait for formal permission to express the truth he saw. With each work, he asked: Who’s watching? Who’s listening?

His Style, His Themes

Motau’s works are primarily charcoal or mixed media on paper, direct, immediate, and unvarnished. One of his most powerful works is titled Apartheid Slave Wagon (1966), charcoal on paper measuring about 60.5 × 132 cm.

In this piece, you see the city’s undercurrents: forced movement, human bodies reduced to cargo, the bleak machinery of power shaping lives. Critics note that this drawing is referenced in the collection of the Constitutional Court of South Africa as emblematic of how art recorded the struggle.

Another example: his drawings of “street beggars” and “township figures” depict bodies hunched, displaced, constrained, but also enduring. His focus was seldom decorative. It was a witness. It was a demand.

His Place Among Peers, in His Time

In 1960s South Africa, black artists faced significant systemic barriers: restricted education, limited gallery access, and marginalisation in mainstream art history. Motau was part of a small generation who, despite the odds, produced forceful modernist work rooted in black urban experience. Because he started young, was self‑taught in part, and worked with urgency, he has a somewhat unique place: he stands between the raw “township art” of survival and the more formal modernism of the era.

What sets him apart further is the brevity of his career: he died in 1968 at the age of 20. His output is small, but intense. That gives his work a tragic resonance and a poignant value: what was made is precious, what could have been is haunting.

Specific Works to Know

Here are a few standout pieces that illuminate who he was and what he did:

• Apartheid Slave Wagon (1966)

This is perhaps his best‑known work. The drawing depicts human figures in a wagon‑like form, drawn with stark lines, heavy charcoal, and dark tones. It powerfully captures the idea of bodies on the move under coercion, under state power, under forced removal. It signals Motau’s interest in movement, displacement, and human endurance.

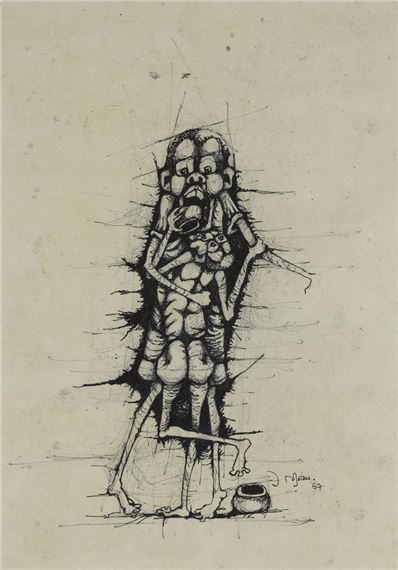

• Street Beggars / Township Figures (circa 1967)

In works like these, Motau zooms in on everyday reality: a figure on the roadside, a child in a township lane, bodies shadowed by city infrastructure. The scenes are minimal yet dense with meaning: survival, waiting, marginalisation. He draws not the glamorous city but the city’s underbelly, untold, unseen, but alive.

• Other Studies of Figures & Urban Life

In works such as Two Figures Looking in a Drum (1967) and Hunger (1967) (both listed in auction records), he explores isolation, multiple bodies in proximity yet separate, and the sense of watching and being watched.

Why He Fits and Why He Still Matters

Motau matters for several reasons:

Authenticity of voice: He was not removed from the world he depicted. He lived the realities of township life and urban migration. That gives his work a grounded, urgent resonance.

Early and brief: His career was extremely short. That rarity gives each work extra weight. He achieved, in a few short years, what many might take decades to attempt.

Social witness through art: His drawings are not just art objects; they are records of a time, a place, a system. They give us insight into what it felt like to live in a space defined by forced relocations, racial segregation, and economic constraints.

Bridging movements: He is a link between the informal, grassroots art that emerged in black townships and the more formal South African modernist art world. His work helps us understand how the personal, the local, the political, and the aesthetic are intertwined in that era.

Risk and scarcity: Because he died young and produced limited work, his pieces face issues of provenance and authentication, and there’s a hunger in the market and among institutions to preserve what remains.

Final Thoughts

Julian Motau’s story is powerful in its paradox: short life, lasting impact; informal training, formal recognition; marginal social space, central human truth. He shows us that art doesn’t have to wait for perfect conditions; sometimes, the urgency of the moment is enough. His drawings ask us to look: at the figure waiting; at the body on the move; at the city that hides its people while depending on them. They also remind us how much of history is lived, not just written.

For anyone interested in art, justice, South Africa’s social history, or in how a young artist under pressure found his voice, Motau stands out as essential. He teaches us that art can speak truth and that even a brief life can leave a lasting imprint.

Comments

Post a Comment